Matrix Operations

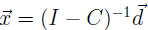

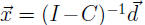

Theorem. If the columns of C each sum to less than 1, and the entries

in

are non-negative, then (I

- C) is invertible, and the production vector

are non-negative, then (I

- C) is invertible, and the production vector

has nonnegative entries and is the unique solution to

has nonnegative entries and is the unique solution to

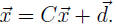

Expanding the problem.

If the external demand is

, the various sectors can produce

, the various sectors can produce

units, but this

units, but this

will create an intermediate demand of

.

.

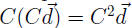

They can then produce another

units. This leads to further intermediate

units. This leads to further intermediate

demand of

units.

units.

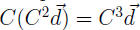

They can then produce another

units. This leads to further intermediate

units. This leads to further intermediate

demand of

units.

units.

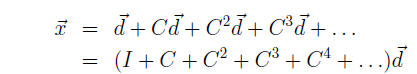

Adding up all of the above, in total the industries have to produce this to

satisfy

the external final demand as well as all of the internal demands that arise as a

result.

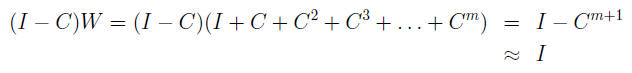

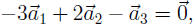

Now for a trick to see this sum in another way. Let

W = I + C + C2 + C3 + . . . + Cm

Then

and so

W - CW = (I - C)W =

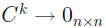

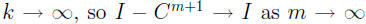

If the columns of C each sum to values strictly less than 1, then

(an

(an

n × n matrix of zeros) as

. And by the

. And by the

Theorem, (I - C) is invertible, and so

which implies

I + C + C2 + . . . + Cm ≈ (I - C)-1

if the column sums of C are less than 1. We can make the approximation as

accurate as desired by making m sufficiently large.

In practice, this can be a useful approximation, especially if the matrix is

large

and sparse (i.e., contains many zeros) and the column sums are significantly

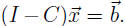

less than one. Even a standard linear system

can be rewritten to use

can be rewritten to use

this trick, by letting C = I -A. Then we can write the system as

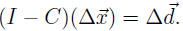

Economic meaning of entries in (I - C)-1.

Given external demand

, say we have found the solution (production vector)

, say we have found the solution (production vector)

satisfying

satisfying

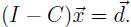

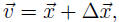

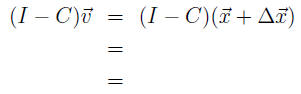

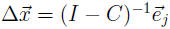

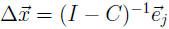

Now consider a new external demand

Say we have solution

Say we have solution

satisfying

satisfying

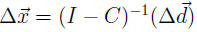

If we let

then

then

because everything is linear.

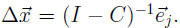

Now say

Then we have solution

Then we have solution

But this is just

But this is just

the _______________________________of (I -C)-1 ! So if we increase external

demand from

up to

up to

, we need to increase production from

, we need to increase production from

to

,

where

,

where

.

.

Result:The jth column of (I - C)-1 says how much extra production will

be needed from all sectors, to meet one additional unit of demand for sector j.

Because the production vector

contains the production levels for each

sector,

contains the production levels for each

sector,

and because

, we can go even further, and get.

, we can go even further, and get.

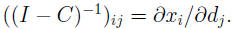

Result :The number in row i, column j of (I - C)-1 says how much extra

production will be required of industry i in order to meet an increase in exter-

nal demand of one unit of sector j, taking into account the new intermediate

demands which arise.

This could also be written as the partial derivative

Section 2.8 { Subspaces, Basis for Null Space and Column Space

Note. examples labeled with Arabic numbers are examples from the book, examples labeled with Roman

numerals are not.

Subspaces

Definition Given a set W of vectors (such as Rn), a subspace of W is any

subset

satisfying three properties.

satisfying three properties.

a. The zero vector is in H

b. If

and

and

are in H, then

are in H, then

. (We say H is closed under addition).

. (We say H is closed under addition).

c. If , then for all scalar constants c, the vector

, then for all scalar constants c, the vector

. (We say H is

. (We say H is

closed under scalar multiplication). Note. this includes c = 0 and c < 0.

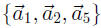

Example 1. span of two vectors.

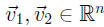

Say

, and H = Spanf

, and H = Spanf . Then H is a subspace of Rn.

. Then H is a subspace of Rn.

Check.

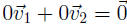

a.

is in the span of

is in the span of

and

and

, so

, so

.

.

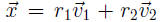

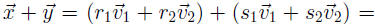

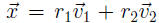

b. If

and

and

, it means

, it means

and

and

for some

for some

constants r1, r2, s1, and s2. Then,

,

which is in H since it is a linear combination of

,

which is in H since it is a linear combination of

and

(and therefore in the span of

(and therefore in the span of

and

and

).

).

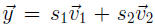

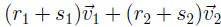

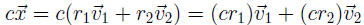

c. If

, it means

, it means

for some constants r1 and r2. Then,

for some constants r1 and r2. Then,

which is in H.

which is in H.

Example 2. Line L in R2 not through the origin.

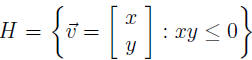

Example III. The set

. (Read the colon as

"such

that" or "satisfying".) Check the three properties.

. (Read the colon as

"such

that" or "satisfying".) Check the three properties.

Example IV. The set

Definition. The column space of a matrix A (written "Col A") is the set of

all linear combinations of the columns of A, i.e. the span of the columns of A.

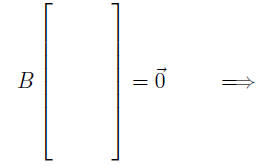

Definition. The null space of a matrix A (written "Nul A") is the set of all

solutions to the homogeneous equation

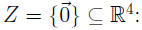

Theorem 12: For an m × n matrix A, the set H =Nul A is a subspace of Rn.

Proof: Note. a vector is in

is in

by definition of this H.

by definition of this H.

Definition. A basis for a subspace H is a linearly independent set in H that

spans H.

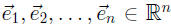

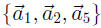

Example V: The vectors

are a basis for Rn. In fact,

they

are a basis for Rn. In fact,

they

are called the standard basis.

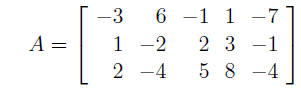

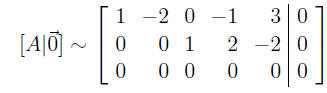

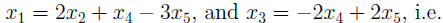

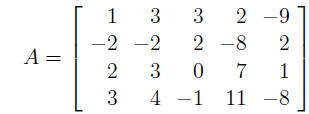

Example 6: Find a basis for the null space of the matrix

Write the solution to

in parametric vector form.

in parametric vector form.

So x2, x4, and x5 are free,

So Nul A =_____________________________

And is a linearly independent set. So in fact it is a basis for Nul

A.

is a linearly independent set. So in fact it is a basis for Nul

A.

This always happens, because.

1. When we write the solution set to

in parametric vector form, the

in parametric vector form, the

solution set is always the set of all linear combinations of the vectors

attached

to the free variables. That is, those vectors always span Nul A.

2. For a general matrix A and the equation

, if xi is a free variable,

, if xi is a free variable,

think about the ith position in each of the vectors in the parametric vector

form

of the solution set to

. That position will be 1 in the vector which

. That position will be 1 in the vector which

goes with xi, and will be 0 in all other vectors. The same holds for the other

free variables. So the only linear combination of those vectors which gives

will be the trivial linear combination, i.e. the vectors will always be linearly

independent.

Result 1:To find a basis for the null space of A, write the solution set to in parametric vector form. The vectors in that form are a basis. in parametric vector form. The vectors in that form are a basis. |

Finding a basis for the column space of A takes less work, but some explanation

for why the technique works.

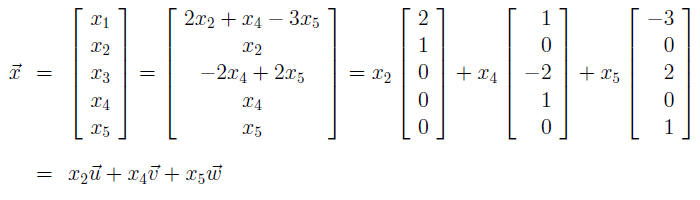

Example 7: Find a basis for the column space of the matrix

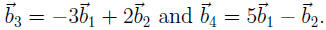

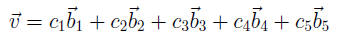

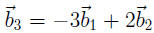

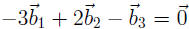

Calling the columns note that

note that

So any linear combination

can really be written as

So in fact

spans

Col B. Also, the set

spans

Col B. Also, the set

is linearly indepen-

is linearly indepen-

dent because those vectors are in fact the vectors

, and

, and

which

is

which

is

clearly a linearly independent set.

Since

, this also means that

, this also means that

. This in

turn

. This in

turn

implies that

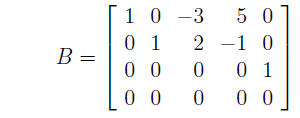

Now consider the matrix

If you check, you will find that A is row equivalent to B on the previous page.

In fact, B = rref(A). The fact that A and B are row equivalent means that

This in turn means that

where

where

are the

columns

are the

columns

of A. So the same tricks we used with B will work for A, and in fact

spans Col A.

Also

is a linearly independent set (you still need to give it a

little

is a linearly independent set (you still need to give it a

little

bit of thought to fill in the details to see this).

| Result 2: (Theorem 13) To find a basis for the column space of A, reduce A to an echelon form to find out where the pivots are (you don't need reduced echelon form). The pivot columns of A form a basis for the column space of A. (Warning: be sure you use the columns of the original A once you find out where the pivots are, and not the columns of the echelon form of A!!!) |